Dmytro Bortniansky (October 28, 1751 – October 10, 1825)

Dmytro Stepanovych Bortniansky (born October 28, 1751, Hlukhiv, Ukraine – died October 10 [September 28, O.S.], 1825, St. Petersburg, Russia), Russian and Ukrainian composer, singer and teacher, the author of operas, a small quantity of chamber music and a vast amount of liturgical music. He was one of the most outstanding figures in the transition between Classical and Romantic periods. The key to Bortniansky’s enormous success is his Italian compositional training. Regarded by both Russians and Ukrainians as a central figure in their music histories, Bortniansky is credited with developing their genre of the sacred choral concerto to its highest forms.

Contents

BIOGRAPHY

Family

Dmytro Bortniansky was born in the town of Hlukhiv, which at the time was a part of the autonomous Cossack Hetmanate within the Russian Empire. His father, Stepan Vasylovych Bortniansky, served as a Cossack under hetman Razumovsky. He married a widow, Maryna Dmytrivna Tolstaya. They had three children, one daughter, Melania, and two sons, Tymofiy, who died at a very early age, and Dmytro. The family lived in the house in the very center of the town, near a noisy marketplace and the ancient Mykolaiv church from where beautiful choral music was heard. In the market square kobzars (wandering minstrels) spun their ballads and heroic tales, they accompanied their singing with a musical instrument called a bandura (kobza). The Kiev Academy students performed comedies saturated with folk songs and dances. Obviously, the first musical impressions of the little Dmytro were associated with these events.

St. Petersburg Imperial Court Chapel period

Marko Poltoratsky (April 28, 1729 – April 24, 1795) Singer, choir conductor, the director of the Imperial Court Chapel in 1763 – 1795

Bortniansky began his musical training at the Hlukhiv choir school, from which talented singers were recruited to the St. Petersburg Imperial Court Chapel. In 1758, at the age of seven, recognized for his outstanding voice and musical abilities, was sent to the Imperial Court Chapel, where he became one of Empress Elizabeth’s favourite choirboys. Bortniansky received general and musical education at the chapel school, he studied music under Ukrainian-born Marko Poltoratsky who was the director of the Imperial Court Chapel. Although physically extricated from Ukraine, Bortniansky maintained cultural ties with his homeland, everything at the court, from the director to the youngest chorister, was Ukrainian. During the reign of Empress Elizabeth the atmosphere of genuine enthusiasm for Ukrainian folk music prevailed. One of the most popular ballroom dances of the time was the inflammatory Ukrainian Kozachok (the transliterated word means Little Cossack) that was often danced throughout Europe.

As one of the most talented choristers, Bortniansky was involved in operatic productions, later it helped him to compose his own operas. In 1764 he played the role of Admetus in Raupach’s Al’tsesta. At the same time, Bortniansky studied dramatic acting at the cadet school where he would also have become familiar with military music. In 1766, as many other choristers of the Imperial Court Chapel, the future composer began studying Italian, French and German, the knowledge of which helped him in the future.

During this period Bortniansky studied composition with a famous Italian composer Baldassare Galuppi who was Kapellmeister at the Imperial Court Chapel. Galuppi’s work at the court was varied, in addition to his duties in the Chapel he staged a number of Italian operas and composed incidental music for various court occasions.

Further musical education in Italy

Baldassare Galuppi (October 18, 1706 – January 3, 1785), Italian composer

In 1769, after Galuppi had left for Venice, Catherine II sent Bortniansky to further his musical education in Italy. Arriving in Venice he continued studying with Baldassare Galuppi (who was then the director of one of the best Italian conservatories). While in Russia, Galuppi noticed the outstanding talents of a young Ukrainian musician. Actually, thanks to his insistent recommendation Bortniansky was sent to study abroad.

During his ten year stay in Italy Bortniansky immersed himself in European Baroque and Renaissance music. He travelled extensively, visiting various musical centres such as Florence, Milan, Rome, Naples, and Bologna, where he also improved his compositional technique with Padre Martini (a leading musician and composer of the period, the teacher of the great Mozart). From 1769 to 1779 Bortniansky composed three opere serie in Italy: Creonte (1776) and Alcide (1778), for Venice and Quinto Fabio (1778), for Modena, several settings of Roman Catholic texts including an Ave Maria (1775), a Salve regina (1776). His setting of the entire Catholic Mass Ordinary in German, Nemtskaya obednya (German Liturgy), may also have originated during this period. While in Italy, Bortniansky took a great interest in collecting paintings.

Return to Russia

Title page of the libretto to Bortniansky’s opera Creonte (premiered in Venice in 1776)

The brilliant success of Bortniansky in Italy was noticed at the Russian court. In 1779 he was ordered to return to Russia. The first meeting of the young composer with Empress Catherine II was quite successful, but the queen, who invited foreign musicians, wasn’t going to replace any of them with Bortniansky. He was engaged only as a staff composer and assistant director at the Bolshoi Dvor (Greater Court). Bortniansky started training singers and composing sacred music for Catherine II, producing probably the bulk of his Orthodox choral music during this period. Starting at the end of 1783, Bortniansky served as Kapellmeister to Catherine’s son Paul I at the Malyi Dvor (Lesser Court). It was located in Pavlovsk, where prominent local and foreign architects built a rare beauty palace surrounded by beautiful picturesque parks.

During that time the French comic opera became increasingly popular in Europe, Paul I and his wife took a great interest in it. In Pavlovsk there was an amateur theater, where the courtiers took part in the performances. Bortniansky composed secular music reflecting the taste of the court, notably three French operas: Le faucon (1786) and La fête du seigneur (1786), Le fils rival, ou La Moderne Stratonice (1787). All are in the style of opéra comique, with short musical numbers simple enough to be performed by amateur visitors. The librettos are written in French, but the music of these operas is neither French nor Italian, it reflects its national character. Performances of the operas were sometimes followed by choral cantatas, presumably composed by Bortniansky as well. Bortniansky also taught the harpsichord and piano to the royal family and wrote several keyboard and chamber works.

Pavlovsk Palace. 18th-century Russian Imperial residence built by Catherine II for her son Paul I in Pavlovsk, nowadays it’s a Russian state museum and public park.

The director of the Imperial Court Chapel

In 1796 Bortniansky’s life changed significantly. After Catherine’s death in 1796, Paul I ascended the throne, on the fifth day of his reign he appointed Bortniansky the director of the Imperial Court Chapel, which after the death of Poltoratsky, remained without a leader, he would retain that office until his death in 1825. Under Bortnyansky’s administration, the musical establishment has reached its peak; he focused most of his attention on the care and training of his own singers. Bortniansky improved the learning process and living conditions of the singers. The chapel increased its membership to 108 singers and expanded its repertory to include Western works such as Haydn’s Creation (performed 1802), Mozart’s Requiem (1805), Handel’s Messiah (1806) and Beethoven’s Christus am Ölberge (1813). His weekly open choral rehearsals and concerts became central to the cultural life of St. Petersburg. Imperial Court Chapel gradually expanded its role from being merely the private choral establishment of the ruling monarch to that of an institution actively influencing, and eventually controlling, church choral singing in the entire Russian Empire.

The exterior of the Imperial Court Chapel

Liturgy for imperial churches

The first Chapel’s publications dates from 1814 when Dmitry Bortniansky was commissioned by Alexander I to compile a setting of the liturgy for use in the imperial churches. The result was a volume entitled

Prostoe penie Bozhestvennoi liturgii Ioanna Zlatousta izdrevle po yedinomu predaniyu upotreblyaemoe pri Vysochaishem dvore (Simple chant for the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom traditionally used at the Imperial Court from the earliest times).

Bortniansky’s liturgy, a two-part setting of the chants most commonly sung in the imperial churches, was first published in August 1814 when the firm of H.J. Dal’mas in St. Petersburg produced 138 copies for use at the court. The following year a further 3600 copies were published at the Treasury’s expense, and were distributed around the parishes in accordance with a Synod decree of 26 July 1815. In 1816, a government decree granted the Imperial Court Chapel the exclusive right to publish sacred music across the Russian Empire, a monopoly that continued into the late 19th century.

Unofficial national anthem of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1816

During his lifetime, Bortniansky’s choral concertos and hymns gained popularity across the Russian Empire and well beyond its borders. The famous hymn Kol Slaven, also known as How Glorious is our Lord in Zion with lyrics by Mikhail Kheraskov was an unofficial national anthem of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1816, and until the October Revolution of 1917, its melody sounded every day at midday from the carillon of the Savior’s Gate in the Moscow Kremlin. Kol Slaven became popular in the UK, where it was known as Russia, St. Petersburg or Wells, but the words of the song were new. The greatest popularity the melody of Bortnyansky’s Kol Slaven gained in Germany with lyrics taken from the poem Ich bete an die Macht der Liebe (I Pray to the Power of Love). Among all his works the most famous remains Cherubic Hymn №7, it was translated into Latin and widely published in Western anthologies. According to legend, Bortniansky’s favourite choral concerto, Vskuyu priskorbna yesi, dusha moya? (Why are you mournful, O my soul?), was sung at his deathbed.

Today, Bortniansky’s music continues its triumphal performance in concert halls of various countries and continents. The legacy of this great composer rightfully belongs to the most remarkable pages of musical culture.

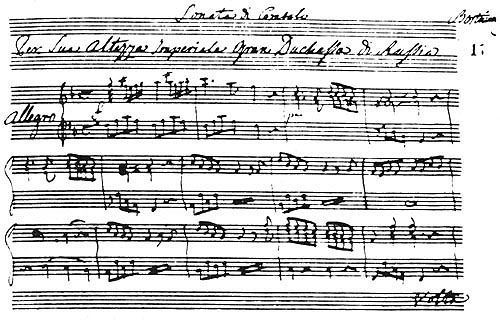

A sample of sheet music, written by Dmytro Bortniansky

SHEET MUSIC

You can find and download free scores of the composer:

0 Comments