Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (21 March 1839 – 28 March 1881)

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, (born March 21 [March 9, O.S.], 1839, Karevo, Russia – died March 28 [March 16, O.S.], 1881, St. Petersburg), is regarded as the most original Russian composer of the mid-nineteenth century, an embodiment of the national style. Largely self-taught and highly intellectual, he discovered a way of writing for the voice that was both lyrical and true to the inflections of speech. He became the source of inspiration for future generations of composers and musicians in Russia and abroad. Mussorgsky was part of a group of composers referred to as The Five (Mighty Handful). He is best known for his opera Boris Godunov, his songs, and his piano piece Pictures at an Exhibition (Kartinki s vystavki).

His life was disjointed, ending in loneliness and poverty, and at the time of his death some of his most important compositions were left unfinished.

Contents

BIOGRAPHY

Family and childhood

Young Modest Mussorgsky as a cadet in the Preobrazhensky Regiment

Modest Mussorgsky was born into aristocratic family. He was the son of a landowner but had peasant blood, his grandmother was a serf. His father served as an official, his mother was a skilled pianist, and she gave Modest his first piano lessons. Modest was a fast learner and quickly mastered the instrument such that within a few years he was giving recitals to friends and family of some difficult and challenging works. At seven he could play some of Franz Liszt’s simpler pieces and by age nine he was able to perform a John Field concerto. Mussorgsky learned about Russian fairy tales from his nurse. His early exposure to Russian folktales inspired him to improvise music even before undertaking formal study. Mussorgsky’s childhood memories are reflected in one of his piano pieces Nursery (Detskaya). Growing up, he heard the peasants on the family estate singing folk songs.

Military education and piano studies

In 1849 Modest’s father took him and his brother, Filaret, to St. Petersburg, where they started to attend the elite Peterschule (St. Peter’s School) in preparation for a military career. It was a family tradition for boys to do military service. At the same time, Modest began piano studies with distinguished teacher Anton Gerke, along with his general studies. In 1852, at thirteen he entered the Guards Cadet School which by all accounts was a particularly harsh regime. There, in his first year he composed his Porte-Enseigne Polka (Podpraporshchik ), published at his father’s expense. In 1856, he joined the Preobrazhensky Guards, one of Russia’s most aristocratic regiments. Though the young Modest had less time for study and practice he was still able to attend piano lessons and played regularly for the other cadets.

Acquaintance with famous people

While still in the military Mussorgsky made the acquaintance of several music-loving officers, among them was Alexander Borodin, a fellow officer who was to become another important Russian composer. The course of Mussorgsky’s musical career changed when he was introduced to Alexander Dargomyzhsky, one of the most influential composers in Russia at that time. At one of the musicales at the Dargomyzhsky’s place, Mussorgsky discovered the music of the seminal Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, and this quickened his own Russophile inclinations. Mussorgsky began developing his own Russian musical style. The following year he was introduced to Mily Balakirev and César Cui, and he also became friendly with the music critic Vladimir Stasov, the main champion of Russian national music. All these people later influenced Mussorgsky’s musical thinking.

The Five (Mighty Handful)

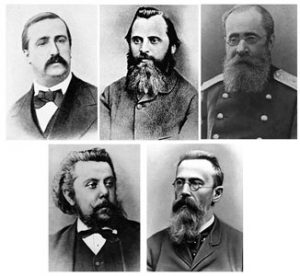

Mussorgsky received from Balakirev lessons in musical form, based on works by Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, and Glinka. This represented the beginnings of The Five (Mighty Handful) whose Nationalist School sought inspiration from the folk music of their homeland. The group’s main goal was to produce a specifically Russian kind of music and not an imitation of older European sounds or European-style conservatory training. The Five’s music was filled with imitative sounds of Russian life, the composers used melodies from village songs, Cossack and Caucasian dances and church chants. When Rimsky-Korsakov joined the group they became five: Mily Balakirev (the leader), Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. With a growing talent for composing, Mussorgsky became part of the group of The Five, but he never managed to make a living from his music.

Balakirev Circle (The Mighty Handful)

Aleksander Borodin, Mily Balakirev (the leader), César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Hard times

In 1858, Mussorgsky resigned from the military in order to dedicate all his energy to music. However, the emancipation of the serfs in 1861 bankrupted Mussorgsky’s family, it required him to spend much time of the next two years helping his brother manage the family estate in Karevo. Since 1863 Mussorgsky had been working as a civil servant in the Ministry of Communications; he remained there in various positions until his dismissal in 1867. Mussorgsky often turned to borrowing money to make ends meet.

Fruitful creative period

In the early days of the Nationalist School, Mussorgsky became known for his song-writing and his ability to follow the natural inflections of his native language. He started working on several operas but failed completing them after losing interest. Among them was the opera Salammbô or The Libyan (Liviyets). In 1861 Mussorgsky composed one of his first and the best symphonic works Intermezzo symphonique in modo classico. In 1863-1866 Mussorgsky wrote a libretto and a voice-and-piano score for six scenes of an opera based on Flaubert’s 1862 novel Salammbô, set in ancient Carthage. After orchestrating three of the scenes Mussorgsky abandoned the project. He later used passages from Salammbô within his more famous opera, Boris Godunov.

Chorus of People in the Temple (Stsena v khrame iz tragedii Sofokla ‘Edip v Afinakh’) is the only completed number from Mussorgsky’s intended incidental music for Sophocle’s play Oedipus, adapted by V.A. Ozerov as Oedipus in Athens.

In 1866, Mussorgsky wrote a series of remarkable songs about ordinary people (which he called “compositions from Russian national life”) such as Hopak, inspired by the episode from Taras Shevchenko’s poem Haydamaky, Darling Savishna (Svetik Savishna), a song about the love of a yurodivy (a holy fool or a village idiot) for a girl named Savishna, he is pathetically pleading for a beautiful girl to accept his love, despite his condition in life. The Seminarian (Seminarist) and Oh, You Drunken Sot! (Akh, ty p’yanaya teterya!), both are studies in one or another form of human depravity, based on texts composed by Mussorgsky himself. During the summer of 1867 he produced several orchestra pieces including the original version of one of his most famous St. John’s Night on Bare Mountain (Ivanova noch na Lysoy gore) which today is often called Night on Bald Mountain (Noch na Lysoy gore), it describes a short story in which St John sees a witches’ Sabbath on the Bald Mountain near Kiev in the old Russian Empire. It’s a wild and terrifying party with lots of dancing but when the church bell chimes and the sun comes up the witches vanish.

The Mighty Handful (Balakirev Circle), 1950. Artist: A. Mikhaylov

Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky (February 14, 1813 – January 17, 1869), an outstanding Russian composer and pianist, had considerable influence on The Five (Mighty Handful).

Alexander Dargomyzhsky’s Portrait, 1869.

Artist: Konstantin Makovsky

Operas The Marriage and Boris Godunov

Like other composers in the Balakirev Circle (The Mighty Handful or The Five), Mussorgsky took an interest in the compositions of Alexander Dargomyzhsky. Inspired by Dargomyzhsky’s Stone Guest (Kamennyy gost’), in 1868 he started to set Gogol’s play The Marriage (Zhenit’ba), Mussorgsky managed to complete the first eleven scenes, but abandoned it after reaching the end of the first act. In 1868 he began his great work Boris Godunov to his own libretto based on the drama by Alexander Pushkin, it is considered to be his masterpiece, with expert musical characterisation. The story tells about the Russian Tsar, Boris Godunov, who ruled Russia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. He killed his rival to become Tsar, but one person (False Dmitriy) knows of his crime and aims to use this against him. The opera Boris Godunov reflected in music the inflections of Russian speech. Being captured by the plot of Boris Godunov Mussorgsky composed the opera very fast. The original version was completed by the end of the year. In 1869 Mussorgsky joined the Forestry Department of the Ministry of State Property. While arranging in 1870 for a production of Boris Godunov, he wrote and published the song cycle The Nursery (Detskaya). In 1871 the first version of the opera Boris Godunov was rejected by the advisory committee of the Imperial Theatres because it lacked a prima donna role. The composer had to make extensive alterations to the score, but the second version, finished in 1871, was rejected as well, only its excerpts were performed in 1873. After several revisions the entire opera was finally produced at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1874 and was an overwhelming success.

Alcohol abuse

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (January 14, 1824 – October 23, 1906) Russian art historian and music critic, one of the foremost figures in 19th-century Russian culture. Vladimir Stasov’s Portrait, 1873. Artist: Ilya Repin

After his mother’s death in 1865, he lived for a while with his brother, then shared a small flat with the Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov until 1872. When his colleague married, left alone, Mussorgsky turned to alcohol. It was a terrible addiction. He spent his nights in seedy taverns, drowning his future in hard liquor. His decline was slow but steady.

Opera Khovanshchina

Being a dipsomaniac, Mussorgsky began his second opera, Khovanshchina (left unfinished at his death, this opera was completed by Rimsky-Korsakov), the idea of composing the opera was suggested by Vladimir Stasov. The opera Khovanshchina tells the story of the revolt of the Streltsy (literally meaning ‘shooter’ in Russian, and easily translatable as ‘musketeer’) led by Prince Khovansky against Peter the Great. Mussorgsky shows how personal and political ambitions can get intertwined, and how the common folk suffer as a result of the power games of their rulers. The opera Khovanshchina was dedicated to Vladimir Stasov who was his adviser; he helped a lot in Mussorgsky’s work searching for the necessary historical documents.

Victor Hartmann and Pictures at an Exhibition

In 1874 Mussorgsky composed the bitter song cycle Sunless (Bez solntsa), where he expressed his despondency, and the set of piano pieces Pictures at an Exhibition (Kartinki s vystavki), inspired by the drawings, stage designs, sketches and paintings of his friend Victor Hartmann, who had died in 1873 at age 39.

Hartmann was a prominent architect and artist whose works were put on display in a memorial exhibition the following year. Inspired by this tribute to his friend, Mussorgsky wrote a large piano work intended to capture ten of the pictures, along with music that depicts someone moving among them in an art gallery. This travelling music, called Promenade, opens the work and returns periodically as an interlude. During 1875 and 1876 Mussorgsky began work on the song cycle Songs and Dances of the Death (Pesni i plyaski smerti). Sunless and Dances of the Death indicate that the composer suffered from depression. Nevertheless, the composer began his comic opera based on Gogol’s story Sorochintsy Fair (Sorochinskaya yarmarka), like other Mussorgsky’s works it was left unfinished.

Final years

Slight relief came in summer of 1879 when Mussorgsky undertook a three-month concert tour of Ukraine, central Russia and the Crimea with the contralto Darya Leonova. The trip created a lot of new positive emotions, but it was not enough to help him overcome his addiction to alcohol. He finally had to leave the government service in January 1880. Mussorgsky continued to appear as Leonova’s accompanist and took a job at her music school in St. Petersburg. In late February 1881 recurrent fits of alcoholic epilepsy required him to be admitted to the Nikolayevsky Military Hospital, where he died shortly after his 42nd birthday. Irregular in his working life and eventually a victim of drink, Mussorgsky in his last days was caught by the painter Ilya Repin in a memorable, ravaged image.

Portrait of M.P.Musorgsky, 1881. Artist: Ilya Repin

Although his completed works are small in number, they are all deservedly popular and viewed as a major contribution to the Nationalist School of music.

WORKS:

BORIS GODUNOV

Fyodor Chaliapin in the title role of the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1912. Artist: A.Golovin

Boris Godunov is in many ways the most Russian of operas, a somber and grandiose spectacle in which the Russian people, both long-suffering and invincible, play the central role.

Opera with prologue and four acts by Modest Mussorgsky to his own libretto based on Alexander Pushkin’s drama The Comedy of the Distress of the Muscovite State, of Tsar Boris and of Grishka Otrepyev (1826) supplemented in the revised version with extracts from Nikolai Karamzin’s History of the Russian Empire (1829). Mussorgsky devoted great energy to this opera, he had to totally revise the score after it was rejected by the advisory committee of the Imperial Theatres and was advised to add a scene with a major female role. The original version focused on the historical Tsar Boris Godunov, who reigned during the so-called Time of Troubles at the turn of the 17th century. Mussorgsky’s opera presupposes that Boris Godunov murdered Dmitri (the true heir to the throne): it becomes the essence of the tragedy, Boris’s suffering guilt that overpowers and destroys him.

Synopsis

The action takes place in Russia between 1598-1605.

Prologue

Scene 1: The courtyard of the Novodevichy Monastery in Moscow, 1598

A ragged and despairing crowd of people are huddled in the courtyard. Guards outside the Novodevichy Monastery order the populace to beg Boris Godunov to accept the throne left vacant after the death of Tsarevich Dmitri. The Police Official terrorizes and intimidates the people; he brandishes a big stick, with which he menaces the crowd and cries: “On your knees!”

The courtyard of the Novodevichy Monastery. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1870. Artist: M.Shishkov

The people lament and sing a chorus of supplication (‘To whom dost thou abandon us, our Father?’ Na kogo ty nas pokidayesh', otets?) A small orchestral introduction depicts the image of the oppressed people, they plead for mercy and pity from Boris Godunov, praying that he will not abandon them to endless misery and squalor like the tsars who preceded him. The mournful theme of the introduction is close to Russian protyazhnaya (folk song).

To whom dost thou abandon us, our Father? ( Na kogo ty nas pokidayesh', otets?), (Boris Godunov, Prologue, Scene 1)

People are indifferent about the elections of the new Tsar. Some of the replicas show that people are not interested in what is happening (‘Mitioukha, say, Mitioukha! Why these plaints?’ Mityukh, a, Mityukh, chego orem?)

Mitioukha, say, Mitioukha! Why these plaints? (Mityukh, a, Mityukh, chego orem?), (Boris Godunov, Prologue, Scene 1)

Andrey Shchelakov, Secretary of the Duma, appears and informs the crowd that the Boyars and the Patriarch have tried to convince Boris Godunov to accept the throne, but he has not relented and refuses to become Tsar (‘Orthodox folk! The boyar remains inflexible.’ Pravoslavnyye! Ne umolim boyarin!) Shchelakov says, if Boris accepts the crown of the Tsar, the misfortunes and suffering of the Russian people will cease.

Orthodox folk! Boyarin remains inflexible (Pravoslavnyye! Ne umolim boyarin!), (Boris Godunov, Prologue, Scene 1)

An approaching procession of pilgrims sings a hymn (‘On earth great is thy Glory, God Creator!’ Slava tebe, Tvortsu vsevyshnemu, na zemle!), they make their way to the monastery, distributing icons and amulets among people. The crowd is urged to reassemble the next day in Kremlin and supplicate themselves before Boris Godunov.

Scene 2: Square in the Kremlin

The bells of Moscow herald the coronation of Boris Godunov. He has relented and agreed to become Tsar. The people kneel and are waiting for Boris. The newly crowned Tsar appears and people praise him. Chorus of greeting by the people to Boris (‘To the sun in all splendor risen be glory! Sing the glory of the Tsar Boris in Russia!’ Uzh kak na nebe solntsu krasnomu slava, slava! Uzh i slava na Rusi tsaryu Borisu, slava!).

To the sun in all splendor risen be glory! Sing the glory of the Tsar Boris in Russia! (Uzh kak na nebe solntsu krasnomu slava, slava! Uzh i slava na Rusi tsaryu Borisu, slava!), (Boris Godunov, Prologue, Scene 2)

Emotionaly stirred, Boris reveals his forebodings and fears of the future and for himself for all Russia. His very first musical characteristic (arioso) reveals a spiritual discord, bad apprehensions (‘My soul grieves!’ Skorbit dusha!)

My soul grieves! (Skorbit dusha!), (Boris Godunov, Prologue, Scene 2)

The new Tsar and the procession enter the Cathedral. The bells resound and the people proclaim: “Glory to the Tsar!”

Act I

Scene 1: Night. A Cell in the Chudov Monastery, 1603

A Cell in the Chudov Monastery. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1900s. Artist: I.Bilibin

Five years have passed after the coronation of Boris Godunov. An old monk, Pimen, is writing the final pages of his chronicle of a gruesome period of Russian history by the light of the icon lamp. Pimen’s Monologue opens the first act. Majestic and concentrated music draws the image of a wise old man. A wandering motive in the bass graphically suggests the passage of monk’s pen as it moves across the parchment.

Pimen’s Monologue, (Boris Godunov, Act I, Scene 1)

Grigory Otrepiev, a fellow monk, suddenly awakens from a horrible dream in agitation and panic. He reveals that it is the third time that he has been haunted by the same frightening nightmare. Pimen reminisces about Ivan the Terrible and his son, Feodor. Pimen says that the murderers of Dmitri, Feodor’s young half-brother, confessed they were sent by Boris Godunov. He notes that Dmitri would now be Grigory’s age. Figuring that he is the same age as the murdered Tsarevich Dmitri, Grigory feels moved by a grand destiny and undertakes to overthrow Boris and conquer the throne. Grigory flees the monastery intending to make his way to Lithuania and Poland and there to establish himself as a miraculously resurrected Tsarevich Dmitri.

Scene 2: An inn near Lithuanian border

Varlaam and Misail, two mendicant monks, and their civilian companion Grigory Otrepiev take refreshment at an inn. Varlaam strikes up a song How it was in the town of Kazan (Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani).

How it was in the town of Kazan (Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani), (Boris Godunov, Act I, Scene 2)

While the monks are drinking and singing, Grigory nervously asks the innkeeper where the road leads. She advises him to be cautious, as soldiers are on the lookout for fugitive and all travellers are being held up. Her directions are interrupted by the police. The officer enters accompanied by the soldiers and orders Varlaam to read the warrant, but he is illiterate and thus unable to read. Then the officer hands the warrant to Grigory to read aloud. Altering the warrant by improvising a description of Varlaam, he convinces them that Varlaam is a fugitive. At this Varlaam becomes enraged, and taking the warrant proceeds to spell his way through it, reading from it a description that tallies very closely with Grigory. The police try to arrest him, but Grigory escapes.

Act II

The Tsar’s Terem (the royal apartments) in the Moscow Kremlin,1605. Tsar’s heir, Feodor, and his daughter, Xenia, with their nurse are together. Xenia mourns her dead fiancé, while her brother Feodor silently studies a map. Xenia’s brother and nurse try to console her, but she cannot overcome her grief. Boris enters, he comforts his sad daughter, and then Xenia and her nurse leave. Feodor shows Boris the map of Russia he has been studying, the Tsar tells his son to study hard. Boris broods about his six year reign with all the power he ever dreamed about but it has brought him no joy. He despondently contemplates his destiny, his sleep haunted by images of a bloodied child.

The Tsar’s Terem. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1870. Artist: M.Shishkov

Monologue of Boris I have attained the supreme power (Dostig ya vysshey vlasti) reveals the depth of the Tsar’s suffering, a long diatribe on his unhappiness, his bad luck.

Monologue of Boris I have attained the supreme power (Dostig ya vysshey vlasti), (Boris Godunov, Act II)

Majestic and strict melody of his aria:

Monologue of Boris I have attained the supreme power (Dostig ya vysshey vlasti), (Boris Godunov, Act II)

Two important reminiscence themes appear in the monologue: the motive associated with Boris’s majesty and authority (‘In vain the soothsayers promise me’ Naprasno mne kudesniki sulyat) and the motive associated with his guilt (‘And even sleep escaped me’ I dazhe son bezhit).

Monologue of Boris And even sleep escaped me (I dazhe son bezhit), (Boris Godunov, Act II)

A boyar announces that Prince Shuisky requests an audience. He brings news that the people are stirred up by the appearance of a false pretender to Boris’s throne. Shuisky alerts Boris that the pretender that appeared in Lithuania is using the name of Dmitri of Uglich. Sending Feodor away, Boris wonders if the murdered boy really was Tsarevich Dmitri. When Shuisky describes the wounds on his body, Boris sees Dmitri’s ghost. Left alone, he begs God’s mercy for his guilty soul.

Act III

Scene 1: Marina Mniszech’s boudoir in Sandomir Castle in Poland, 1604

Marina Mniszech’s Boudoir. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1870. Artist: M.Shishkov

Marina Mniszech, the governor’s daughter, is sitting at her dressing table. Young girls entertain her, praising her beauty with a song. Marina dreams of becoming Tsarina. She intends to win Grigory in order to realise her ambition of ascending the throne of Russia. The Jesuit Rangoni enters; he is determined to convert Orthodox Russia to Catholicism. Rangoni urges Marina to seduce and exploit False Dmitri for the interests of Poland. She protests and says that she is powerless to fulfill such mission, but Rangoni insists that her beauty is her most powerful weapon.

Scene 2: Mniszech’s Sandomir Castle. A Moonlit Night. A Garden. A Fountain

Garden of Mniszech’s Castle. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky, 1870. Artist: M.Shishkov

The False Dmitri is awaiting the beautiful Marina tormented by his passion. The cunning Jesuit Rangoni emerges from the shadows and tells Dmitri how much Marina loves him and how true she is to him. Rangoni and Dmitri conceal themselves as the guests emerge from the palace, among them Marina, leaning on the arm of a Polish noble. Polonaise is heard. The guests toast, compliment Marina and discuss their imminent conquest of Russia. After the numerous guests reenter the palace, Dmitri emerges from hiding. Marina comes. She interrupts Dmitri’s lovesick confession with some matter-of-fact inquires into his political prospects and her future as Tsarina. She announces that only the Russian throne tempts her. Marina scornfully insults and mocks Dmitry callously. Angered, he responds that, once crowned, he will laugh at her. Suddenly Marina pledges her love.

Act IV

Scene 1: The Square before the Cathedral of Vasiliy the Blessed in Moscow, 1605

A crowd of impoverished and starving people is discussing Dmitri’s victories over the forces of Boris. Mitioukha tells that Grishka Otrepiev (False Dmitri) is cursed in the Cathedral and a requiem mass is conducted for Dmitri of Uglich (the true heir to the throne). The Yurodivy (the holy fool or simpleton) enters, pursued by the band of urchins. He sings a nonsensical song (‘The moon sails on, the kitten cries’ Mesyats yedet, kotyonok plachet)

The moon sails on, the kitten cries (Mesyats yedet, kotyonok plachet), (Boris Godunov, Act IV, Scene 1)

The urchins surround and tease him and steal the kopek. When Tsar Boris exits from the Cathedral, the hungry people beg for bread (‘Bread, give bread to the hungry, Father, for Christ’s sake!’ Khleba, khleba! Day golodnym khleba, khleba! Khleba poday nam, batyushka, Khrista radi!)

Bread, give bread to the hungry, Father, for Christ’s sake! (Khleba, khleba! Day golodnym khleba, khleba! Khleba poday nam, batyushka, Khrista radi!), (Boris Godunov, Act IV, Scene 1)

As the chorus subsides, the Yurodivy’s cries are heard. There follows the searing exchange between the Tsar and the Yurodivy, who is usually portrayed as the voice or personification of the people. Boris asks why he cries. The Yurodivy tells that the boys have stolen the kopek and asks Boris to slit their throats (to kill them as he killed the young Tsarevich). Boris asks for his prayers, but the Yurodivy refuses to pray for the “Herod Tsar.”

Ivan Semyonovich Kozlovsky (1900-1993) was a legendary Soviet opera tenor and a soloist.

Kozlovsky as the Yurodivy in the opera BORIS GODUNOV by M. Mussorgsky

Scene 2: The Palace of the Facets in the Moscow Kremlin, 1605

The Palace of the Facets. Stage design for the opera Boris Godunov by M. Mussorgsky

A session of the Duma of Boyars has met and is considering what judgment shall be meted out to the Grigory Otrepiev. He must be caught, tortured and hanged and who follow him, are to die. Shuisky arrives and informs the boyars that Tsar Boris is deranged. Disbelieving him, the boyars are stunned into silence, the tormented Boris appears at the council, imagining little Dmitri alive. Pimen enters and tells the Tsar how an aged shepherd had come to him and informed him that in a vision he had been bidden to go to the city of Uglich and into the Cathedral there and pray at the tomb of the young Tsarevich Dmitri, and that as soon as he had done so, his blindness would be cured. The news causes Boris to erupt a fatal seizure. Before he dies, Boris names his son Feodor his successor, and begs forgiveness for his crimes.

Scene 3: A forest clearing near the town of Kromy

A crowd of vagabonds and peasants have risen against Boris and have captured the boyar Khrushchov, and sing him a song (‘Not a falcon soaring across the sky’ Ne sokol letit po podnebes’yu). The people mock the boyar, revenging for all their humiliation. The people then erupt into their ferocious chorus of anarchy and revolt (‘Valiant daring has become enraged and broken loose’ Raskhodilas’, razgulyalas’ sila, udal’ molodetskaya).

Valiant daring has become enraged and broken loose (Raskhodilas’, razgulyalas’ sila, udal’ molodetskaya), (Boris Godunov, Act IV, Scene 3)

Varlaam and Misail join in this chorus and urge the crowd to join the forces of False Dmitri against Boris. The chorus culminates in cry, “Death to Boris! Death to Boris! Death to regicide!” The Russian people join Dmitri and march to Moscow. The Yurodivy is left alone to bewail the fate of Russia. As he sings a poignant lament for the land and its suffering people, the curtain falls.

PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION (Kartinki s vystavki)

Modest Mussorgsky created Pictures at an Exhibition under a strong impression of the memorial exhibition of sketches and watercolours by the painter and architect Viktor Hartmann (who died at the peak of his career in July 1873 at age 39).

Viktor Alexandrovich Hartmann (1834 –1873) was a Russian painter and architect

Modest and Viktor were close friends and both shared a commitment to Russian nationalism. Mussorgsky was shocked by Hartmann’s unexpected death. The loss of not just a close friend but also an artistic inspiration had a profound effect on Mussorgsky and the wider artistic community in Moscow. The organizer of the memorial exhibition was Vladimir Vasilyevich Stasov, an authoritative critic in both art and music. Stasov also wrote the programme in Mussorgsky’s original score, imagining a spectator promenading round the show. Although originally composed in June 1874 for solo piano, Pictures at an Exhibition became better known in orchestral form, vivid pictorialization and textural variety within the piano score caught the ear of Serge Koussevitsky, and he commissioned Maurice Ravel to create an orchestral version which was premiered at the Paris Opera on October 19, 1922. There’s no

record of a public performance of Pictures at an Exhibition in Mussorgsky’s lifetime, the piece had been neither performed nor published. It was left to his friend and colleague Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov to tidy up the manuscript and bring it to print in 1886.

Mussorgsky may well have had an inflated impression of Hartmann’s artistic importance (as friends often do), but these Pictures guaranteed Hartmann a place in history that his art alone never could have achieved. The composer was inspired to capture the spirit of Hartmann’s works. The suite consists of musical depictions of ten paintings, interspersed with a recurring Promenade (Progulka) theme, or intermezzo, this gives listeners the impression of enjoying a leisurely stroll into and through the gallery, moving from one of Hartmann’s images to the next each time the Promenade music is heard. Mussorgsky links his sketches together with a musical Promenade in which he depicts himself moving from one picture to the next. The theme is totally independent of Hartmann’s material and appears in variations that convey Mussorgsky’s mood and feelings as he moves from picture to picture.

Promenade (Progulka), Pictures at an Exhibition by M. Mussorgsky

With the Promenade we enter not any gallery but one filled with purely Russian art. Promenade is a piece with characteristic features of Russian folk songs. During the cycle the music character of the Promenade changes under the influence of the different moods.

The first picture is Gnome (original title in Latin ‘Gnomus’). Hartmann’s design was a carved wooden nutcracker for a Christmas tree. The ornament was in the shape of a gnome and a nut was put into his mouth to crack. In the music, which portrays the dwarf’s awkward leaps and bizarre grimaces, are heard cries of suffering, moans and entreaties.

Cathedral Tower in Périgueux. Artist: Viktor Hartmann

The second picture of the cycle is The Old Castle (original title in Italian ‘Il Vecchio Castello’). An old tower of the Middle Ages, in front of which a troubadour sings his song, a long, unspeakably melancholy melody. The troubadour, who is unsuccessful in wooing his sweetheart, is represented by the doleful tones of alto saxophone. The music ends quietly with throbbing rhythms. Many take it to be based on Hartmann’s sketch of the old French Cathedral Tower in Périgueux. Some point out that if Mussorgsky wanted to depict the old French cathedral from Hartmann’s sketch, he could have chosen a French title for this. The Italian title suggests that this was one of Hartmann’s watercolour sketches done in Italy, but there were some architectural sketches from France in the exhibition catalog, none were from Italy.

The Old Castle, Pictures at an Exhibition by M. Mussorgsky

Next picture is the Tuileries (original title in French ‘Tuileries (Dispute d’enfants après juex)’), the French title of this little scherzo translated as ‘children quarrelling after play’. Tuileries, a sprightly sketch of children at play in the well-known Tuileries Gardens in Paris. The ‘voice’ of the noisy children as they play and quarrel together and the scolding of their nurse are clearly heard in this musical picture. The music moves lightly, quickly, full of sparkle and delight. Tuileries is an example of composer’s ability to portray the world of children. Mussorgsky was liked by and was popular with them; he understood children and loved their creative imaginations and sincerity.

Cattle (original title in Polish ‘Bydło’), is used to head the musical depiction of a lumbering large Polish ox-cart. The melody is a folk song, presumably sung by driver. The heaviness of the cart and the oxen is presented via solo tuba and slowly moving orchestration thumping in 4/4 meter. The music quiets as the cart moves away at the close.

Sketch of Costumes for the Ballet Trilby by J. Gerber. Artist: Viktor Hartmann

Following Cattle is Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks (original title in Russian ‘Balet nevylupivshikhsya ptentsov’). This watercolour sketch is one of the few remaining examples of Hartmann’s work as a stage and costume designer. Hartmann designed costume sketch for children dancers in a ballet entitled Trilby. One of the costume sketches showed a child with only arms, legs and head protruding through a large chicken shell. The score is written in the upper registers of the piano and skilfully imitates the clucking of chickens and the fluttering of their feathers.

Next picture is the caricature of two Jewish men – Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle (original title in Yiddish ‘Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle’). The sixth scene evokes an image of Two Jews: A Rich Jew Wearing a Fur Hat and A Poor Sandomir Jew through the interplay of a strident melody in the lower register and a twittering chantlike theme in the upper.

A Rich Jew Wearing a Fur Hat. Artist: Viktor Hartmann

A Poor Sandomir Jew. Artist: Viktor Hartmann

The Hartmann’s wife was Polish. In 1868 he visited a small town of Sandomir, in southern Poland. There he painted scenes and characters in the Jewish ghetto, including these two men, as well as Cattle. In Hartmann’s paintings the rich man looks self-assured, proud, and full of dignity. The poor man, on the contrary, looks feeble and frail. He dejectedly sits in the street wearing rags with his head hung low, holding nothing but a stick in his hands. The music uses these two Jewish stereotypes into one representation. In the opening section with the decisive and highly ornamented theme, the first (Samuel) ‘speaks’ in an imperative and assertive fashion. The second (Schmuÿle) ‘speaks’ in the second section – chanting high voice used during ritual davening (praying) in synagogue. In the final section, the first and second themes are fused together.

Limoges. The Marketplace (The Big News) (original title in French ‘Limoges. Le marché (La grande nouvelle’). Hartmann painted many watercolours in the town of Limoges. This picture is the wonderful portrayal of French marketplace, with women that are furiously gossiping, chattering and quarrelling behind their carts. The folksy and cheerful quality of the seventh movement, Limoges. The Marketplace (The Big News), is neutralized by the eighth, The Catacombs.

Catacombs (with Viktor Hartmann, Vasily Kenel, and a guide holding the lantern). Artist: Viktor Hartmann

The Catacombs (A Roman Burial Chamber) (original title in Italian ‘Catacombae (Sepulcrum romanum)’) casts an eerie shadow with ominous chords and variations on the recurring intermezzo. The drawing showed Hartmann himself with a fellow architect Vasily Kenel in the Paris catacombs and a guide holding lamp. The catacombs symbolize death and the helplessness of humans to fight its inevitability.

The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba-Yaga). Artist: Viktor Hartmann

The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba-Yaga) (original title in Russian ‘Izbushka na kur’ish nozhkah (Baba-Yaga)’) Hartmann sketched a clock of bronze and enamel in the shape of the hut of Baba-Yaga (a fearsome witch in Slavic mythology who lives in the deep forest in a hut that stands on chicken legs). She also uses her mortar to ride through the sky, Mussorgsky added the suggestion of her wild flight at the end of this number.

The final picture is The Bogatyr Gate (In the Ancient Capital Kiev) (original title in Russian ‘Bogatyrskiye vorota (V stol’nom gorode vo Kiyeve). Hartmann’s design was his entry into a competition for a gateway to be erected at Kiev but the competition was called off and the gate was never built. Hartmann modeled his gate on the traditional headdress of Russian women, with the belfry shaped like the helmet of Slavonic warriors. The musical picture is unsurpassed in grandeur and majesty and processes unquestionable Russian national character. Mussorgsky’s piece, with its magnificent climaxes and pealing bells, finds its ultimate realization in Ravel’s orchestration.

Design for Kiev City Gate. Artist: Viktor Hartmann

SHEET MUSIC

You can find and download free scores of the composer:

4 Comments

Vitalii · 27.03.2017 at 17:03

Mussorgsky’s one of my favorite composers.

Daniella · 14.06.2017 at 15:29

Greetings! Really helpful guidance on this article!

It’s the little changes that make the biggest changes.

Thanks a lot for sharing!

Felipa · 19.06.2017 at 03:53

This is a subject close to my heart cheers. Thanks

james frazer mann · 15.08.2017 at 10:35

Great post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m

impressed! Extremely helpful information particularly the last

part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was looking for this certain information for a

very long time. Thank you and best of luck.