Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (June 1, 1804 – February 15, 1857)

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (born June 1 [May 21, O.S.], 1804, Novospasskoye, Russia – died February 15 [February 3, O.S.], 1857, Berlin, Germany), a famous Russian composer who is often referred to as the father of Russian classical music. Music historians proclaimed him the first composer able to express the Russian national spirit and Russian ambitions in music, thanks especially to his imaginative treatment of Russian folk song. Although Glinka was not the first Russian composer to adopt a style based on folk melody, he was far more gifted than his predecessors. A Life for the Tsar shows his dramatic power. Ruslan and Lyudmila was less successful as drama, but its lyrical melodies, daring harmonies, brilliant orchestration, and orientalism influenced much subsequent Russian music.

Contents

BIOGRAPHY

Family

Mikhail Glinka was born in 1804 in Novospasskoye near Smolensk, into a family of landowners. His father, Ivan Nikolayevich Glinka, though only twenty-seven, had already resigned his commission in the army. His wife was a girl of nineteen. The parents of the future composer were smart, well-educated and had a fine aesthetic taste. They had thirteen children, some of them died prematurely, Mikhail was the eldest surviving child. He spent the first years of his life in his father’s manor, living there he developed love for the local folk music which remained with him for life.

Childhood and the first experiences with music

Glinka’s first experiences with music came from the peasant folk songs of servants and from the church bells, both of which greatly intrigued him. His nanny, Avdotya Ivanovna, was able to cultivate in him love for national folklore while telling amazing fairy tales and singing folk songs. His first six years were spent in the company of his autocratic grandmother, who nearly ruined him. Mikhail’s grandmother not only spoiled him by giving him everything he wanted, but insisted on wrapping him in furs and keeping him in her overheated room. He grew feeble, nervous and sick child, manipulated by his over-protective grandmother until she died in 1810. After her death, Glinka returned to his parents and his musical horizons broadened.

The image of the manor house in Novospasskoye where Mikhail Glinka was born.

In August of 1812, Napoleon’s army invaded Smolensk region. Fleeing from the invasion, the family left the manor and temporarily settled in Orel. During the time, the boy heard many stories about the heroes of that war, later those stories were reflected in his works. In 1813 the family returned to Novospasskoye, Mikhail’s father repaired (and in fact, built anew) a manor house.

Serf orchestra

Glinka first became interested in music at age 10 or 11, his uncle retained an orchestra made up of serfs. Mikhail discovered overtures and symphonies by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. However, it was a clarinet quartet by Bernhard Crusell that awoke in Glinka his lifelong passion for Western music. The orchestra would often play Russian folk songs. Glinka was so captivated by their music that he would often stand perfectly still while listening to them or try to pick up an instrument and join in. The future musician was especially charmed by the sounds of the violin and flute. He even conducted the orchestra at times when he got older. Music produced such an indelible impression upon Mikhail that he asked to be taught music along with the lessons of Russian, German, French and geography that his governess, Varvara Klammer, was in charge of.

A portrait of Mikhail Glinka as a young man

Education

In 1817 Mikhail’s parents sent him to St. Petersburg to study at the school for children of the nobility at the Chief Pedagogic Institute. His favourite subjects were languages – Latin, German, English, French and Persian, he also liked geography and zoology. Music was not included in the curriculum of the Institute, but none the less Glinka was sent to the best available masters in St. Petersburg. He took piano, violin and voice lessons from the Italian, German, and Austrian teachers there. The deepest impression was made by the lessons of the famous Irish pianist and composer John Field, later he studied with Charles Mayer. It was to Mayer that Glinka was indebted for most of his musical education. By 1822 he was able to play Hummel’s A minor Concerto in public, accompanied by Mayer on a second piano.

Trip to the Caucasus

In 1823 Glinka went to the Caucasus for the mineral water cure at Pyatigorsk to improve his health. The treatment disagreed with him. But Glinka was touched by the majestic nature of the mountainous Caucasus, exotic plants, folk music and dances, different from everything he had heard and seen before. The Caucasian theme was reflected in his later works.

Return to Novospasskoye

After a trip to the Caucasus, he returned to Novospasskoye, where he became deeply involved in the rehearsals of his uncle’s orchestra – a luxury available to few young composers. The orchestra helped him practically improve the knowledge of instrumentation. He composed much and stayed in the village until April 1824.

Civil service

After spending some time with the family in Novospasskoye, Glinka returned to St. Petersburg. In 1824, he followed his father’s wishes and joined the Foreign office as assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways, he worked there for four years but was uninterested in an official career. He did not enjoy the civil service, but the work was easy, allowing much free time to socialize and compose, mostly romances aimed to entertain his high-society public. As a dilettante he composed songs and a certain amount of chamber music.

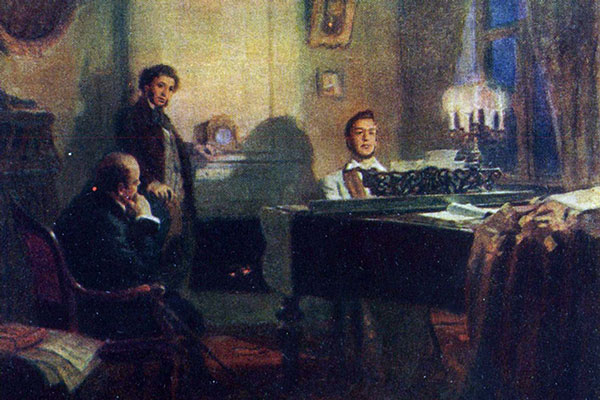

Pushkin and Zhukovsky at Glinka’s place, 1953. Artist: Victor Artamonov

In St. Petersburg Glinka became acquainted with such leading literary figures as Pushkin, Delving, Zhukovsky and Griboyedov. By that time, the young composer was already the author of many romances and piano pieces. But only a tiny handful have permanent value. The music composed during this time was lacking in individuality, Glinka imitated what he heard, be it works by Rossini, Haydn, Mozart, or Beethoven, or merely dance music. In 1825 he composed Do Not Tempt Me Needlessly (Ne iskushay menya bez nuzhdy) based on the words by Baratynsky. The romance belongs to the number of the best sentimental-lyrical vocal works of the young Glinka.

The Decembrist revolt

The year 1825 marked a watershed in Glinka’s creativity. At the end of the year, the young man witnessed the events that shocked him. On December 14 [December 26, New Style], early in the morning, Glinka came to the Senate Square, where he stayed for a long time. That tragic and gloomy cold day a group of officers commanding about three thousand men assembled in Senate Square, where they refused to swear allegiance to the new tsar, Nicholas I, proclaiming instead their loyalty to the idea of a Russian constitution. They expected to be joined by the rest of the troops stationed in St. Petersburg, but they were disappointed. Nicholas spent the day gathering a military force, and then attacked with artillery.

The Decembrist Revolt at the Senate Square on December 14, 1825, a painting by Vasily Timm

With the firing of the artillery came the end of the revolt. In the center of the square Glinka saw the faces of people he knew, among the Decembrists he saw his teacher Wilhelm Küchelbecker and boarding comrades. Glinka became involved in political trouble, he was suspected of having aided Küchelbecker. Glinka was interrogated but had no difficulty in clearing himself. Not wishing to stay in St. Petersburg anymore, Glinka left for Novospasskoye, and in January 1826, he went to Smolensk, but a change of scene did not bring him relief. The horrors of unsuccessful and bloody revolt left a mark on his music. The notes of anxiety, melancholy and loneliness appeared in his works. In those days he composed one of the most tragic works – The Poor Singer (Bednyi pevets) based on the words by Zhukovsky.

Trip to Italy

In 1830 Glinka left for Italy upon the recommendation of a physician, he needed a warm climate to restore his failing health. He had a wish to study Italian opera in its country of origin. There he fell in love with Italian culture became a friend of Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini. But Glinka’s interest in Russian music continued even there, he not only wrote a group of pieces based on Russian themes, but also began to plan a Russian opera. Glinka spent three years in Italy listening to trendy music and meeting famous people including Mendelssohn and Berlioz.

Vienna and Berlin

On his way back to Russia from Italy, he travelled through Vienna, where he first heard music of Franz List. In Vienna he also heard the orchestras of Strauss and Lanner. He stayed for five months in Berlin, where he took a course in counterpoint and general composition with Siegfried Dehn (one of the most respected musical theorists of the time). Glinka composed two important works during this time, A Capriccio on Russian themes and an unfinished Symphony on two Russian themes. Glinka was nearly 30 when he completed his theoretical education.

Two operas

In 1834 he received the sad news of his father’s death and returned quickly to Novospasskoye. During the next two years he was occupied with the composition Ivan Susanin, to a libretto by Georgy Rosen. Shortly before the 1836 premier, the tsar suggested that the opera should be renamed A Life for the Tsar (Zhizn’ za tsarya). The work was enthusiastically received. He began almost immediately on his next opera, a setting of Valerian Shirkov’s libretto based on Pushkin’s poem Ruslan and Lyudmila.

Personal life

Anna Kern, best known as the addressee of love poem I recall a wonderful moment (Ya pomnyu chudnoye mgnoyen’ye), written by Aleksandr Pushkin in 1825.

In 1835 Glinka married Maria Petrovna Ivanova, but their marriage was foredoomed to disaster. Maria had absolutely no interest in music. She was very beautiful, but she was a coquette and fool.

Ekaterina Kern, Anna Kern’s daughter, who inspired Glinka on the creation of the romance, I recall a wonderful moment (Ya pomnyu chudnoye mgnoyen’ye).

Glinka remembered his wife flirting with men, being rude to him and spending more money than the family could actually afford. The marriage was unhappy and their relationship didn’t last long. In spring 1839 during one of the evenings Glinka enjoyed at his sister’s place he first saw Ekaterina Kern, daughter of his old acquaintance Anna Kern, the lady whom Pushkin had celebrated in lovely verse. Pushkin wrote a poem I recall a wonderful moment (Ya pomnyu chudnoye mgnoyen’ye) that reflects the episodes from Pushkin’s life when he met Anna, later Glinka who was in love with Anna Kern’s daughter Ekaterina, set this poem to music. In autumn 1839 he found out about his wife’s unfaithfulness and left home. He soon became separated from his wife, finally divorcing her in 1846.

Mikhail Glinka and his sister Lyudmila Shestakova

Kapellmeister of the Imperial Chapel

In 1837 Glinka was appointed Kapellmeister of the Imperial Chapel, this position was created especially for him. Mikhail had recently won the tsar’s favour with production of his opera A Life for the Tsar. His duties included supervision of the other teachers, and the training of soloists. During the next few years various projects interrupted work on the opera. In 1838 he set a number of Pushkin’s poems, including Where is our rose? (Gde nasha roza?) and I recall a wonderful moment (Ya pomnyu chudnoye mgnoyen’ye). In 1839 he was sent to Ukraine for three months to recruit singers for the Imperial Chapel. From this period dates the most famous of all Glinka’s songs, his setting of Zhukovsky’s Midnight Review (Nochnoy smotr). A set of 12 songs followed in 1840, as well as incidental music to the play Prince Kholmsky (Knyaz’ Kholmsky).

Ruslan and Lyudmila

In 1842 his second opera, Ruslan and Lyudmila, was produced. The exotic subject and boldly original music of Ruslan won neither favour nor popular acclaim, although Franz Liszt was struck by the novelty of the music. Ruslan and Lyudmila was not well-received by the public or critics, and was withdrawn from the repertoire in 1848, it gained popularity later. Disappointed by this, Glinka remained inactive for the next year.

Trip to France and Spain

In 1844 Glinka left Russia. He travelled to France and Spain. In Paris Mikhail made friends with Hector Berlioz and studied the French composer’s work. The following year he went to Spain, where he stayed until May 1847, collecting the materials used in his two Spanish overtures, the capriccio brillante on the Jota Aragonesa (1845) and Summer Night in Madrid (1848). In 1848 Glinka composed the occasional concert piece – the Kamarinskaya. During this time he also wrote songs, many of which were influenced by Chopin’s style – Adèle (Adel’), The Toasting Cup (Zazdravniy kubok), The Gulf of Finland (Finskiy Zaliv).

Last years

Between 1852 and 1854 he was again abroad, mostly in Paris, until the outbreak of the Crimean War drove him home again. He then wrote his highly entertaining Memoirs (Zapiski), which give a remarkable self-portrait of his indolent, amiable, hypochondriacal character. His last notable composition was Festival Polonaise for Tsar Alexander II’s coronation ball in 1855.

In 1856 Glinka went to Berlin to study Western contrapuntal techniques with Dehn. While in Berlin Glinka had frequent contact with Giacomo Meyerbeer. Mikhail Glinka died in Berlin a few weeks after catching cold. He was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to St. Petersburg and reburied in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

Glinka’s music was posthumously edited first by Balakirev, and then later, on his centenary, reedited by Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov of publication by Edition M.P. Belaieff.

WORKS:

A LIFE FOR THE TSAR (Zhizn’ za tsarya; Ivan Susanin)

Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar is a heroic folk musical drama. The opera’s story, drawn from Russian history, tells about the heroic deed of the Kostroma peasant Ivan Osipovich Susanin who in 1612 saved the life of the first of the Romanov tsars at the cost of his own. Opera in four acts and epilogue. The libretto was originally written by Baron Rosen and during the Soviet era it was rewritten by Sergei Gorodetsky.

Back in Russia, Glinka’s first idea was to adapt Maryna roshcha (Mary’s grove), a short story by the poet Vasiliy Zhukovsky. That author, however, suggested that the use of the story of Ivan Susanin instead. Collaboration with Zhukovsky, Sologub and Kukolnik having proved unproductive, Baron Rosen, the final choice, appeared just right man to fit words to the music. They worked together on the opera for two years, then in 1836 they rehearsed it in the presence of the tsar himself, who was so taken by its fervent patriotism that he proposed the alteration of its name from Ivan Susanin to A Life for the Tsar.

A Life for the Tsar was the first nationalist Russian opera, premiered in St Petersburg in 1836 and was well-received by both the tsar and the public. During the Soviet era A Life for the Tsar underwent changes in libretto and the opera was known under the name Ivan Susanin. The original version was revived in 1989 in Moscow and still often performed.

Synopsis

Domnino. Stage design for the opera A Life for the Tsar by M. Glinka, 1939. Artist: Peter Williams

Act I The village of Domnino

The village of Domnino in which Ivan Susanin, a humble but heroic peasant, dwells with his daughter Antonida and Vanya, his adopted son. The peasants rejoice at a Russian victory against the invading Poles. Antonida is waiting for her fiancé, Bogdan Sobinin, who defends the homeland from enemies. She dreams about the forthcoming wedding, but her father does not think the time is right for his daughter to marry. Susanin tells his daughter that there can be no wedding until the Poles are defeated. He is oppressed with a fear of that all is not yet well. When Sobinin announces that Mikhail Romanov is to be crowned Tsar in Moscow, Susanin gives his consent to the marriage of his daughter and Sobinin.

Act II A magnificent ball in a Polish commander’s residence

Couples are dancing a polonaise. The Poles boast of their victories and are confident that Russia will be conquered soon. The dancing continues with a krakowiak and waltz. A messenger bursts in with news of their defeat and the election of Mikhail Romanov, who would displace the Polish prince Wladyslav as a chief claimant to the throne. The majority stays to dance, but a group of Polish soldiers determine to kidnap Romanov from the monastery in which he is living.

The second act contrasts with the first. The musical characteristics are completely different. Instead of a simple heartfelt song and folk choruses the dance music sounds. Three dances (brilliant Polish polonaise, krakowiak, and mazurka) form a kind of symphonic suite only from Polish dances.

The action is opened with a brilliant polonaise.

Polonaise (A Life for the Tsar, Act II)

In the plot-dramatic development of the opera, the scene of the ball is of great importance. Glinka found many bright and imaginative strokes in the music of national dances that accurately characterize the Polish nobility – proud and arrogant.

Scene from the opera A Life for the Tsar (Ivan Susanin) by M. Glinka, End 1830s. Artist: Gagarin, Grigori Grigorievich

Act III Susanin’s izba (or cottage)

During preparations for Antonida’s wedding Polish soldiers break in and demand that Susanin lead them to Romanov’s monastery. At first Susanin refuses indignantly, but after threats he pretends to agree to the Pole’s demands. He tells Vanya that he will try to take the Poles off on a false trail and that Vanya must hasten to the monastery to warn Romanov’s people of imminent danger. Susanin advises Antonida not to delay her wedding. She is deeply upset to see her father leave with the enemies, she realizes the Poles will kill her father. Antonida falls on a bench weeping. On Sobinin’s arrival he hears what has happened and at once organizes a pursuit.

Vanya’s song When they killed the mother of the little bird (Kak mat’ ubili u malogo ptentsa) opens the third act and serves as a musical characteristic of the orphaned boy. Vanya sings a simple and heartfelt song expressing gratitude and devotion to his foster father. Vanya’s song is close to Russian folk songs.

Vanya’s song (A Life for the Tsar, Act III)

The quartet of Susanin, Vanya, Antonida and Sobinin comes next. After interruption of Susanin’s quiet family happiness by the sinister arrival of the Polish detachment in the marvelous scene of Susanin with the Poles in his cottage, the Polonaise and the mazurka become integral parts of the tragic action alongside the struggle going on in Susanin’s heart.

The bridal chorus with its modal cadences, 5/4 rhythm, virtual pentatoncism and unharmonized cantilena in the second half, is perhaps the best overall example of the folk influence.

Bridal chorus (A Life for the Tsar, Act III)

Antonida’s song Not for that do I grieve, dear friends (Ne o tom skorblyu, podruzhen’ki) is one of the most poetic parts of the opera. The song’s melody is simple and heartfelt, the intonations of folk lamentation are heard in it. The song reveals the depth of Antonida’s grief and thus shows the beauty of her inner world.

Not for that do I grieve, dear friends (A Life for the Tsar, Act III)

Act IV

Scene I. A forest glade; night

Sobinin and his followers arrive, having lost their way in the dark. Sobinin encourages them. (Aria ‘Brothers, into the storm’ Brattsy, v metel’).

Scene II. The gates of the Kostroma monastery

Vanya arrives on foot, exhausted. He beats on the door for a long time before anyone stirs. Vanya rouses the inhabitants and warns them of danger to the Tsar (‘My poor horse has fallen in the field’ Bednyy kon’ v pole pal).

Ivan Susanin, 2002. Artist: Maxim Fayustov

Scene III. A dark snow-bound forest. Susanin and the Polish soldiers set up camp for the night, and Susanin broods on his fate (Aria ‘You will come, my dawn?’ Ty vzoydosh’, moya zarya). Susanin reminisces about his family and bids them a vicarious farewell. A storm blows up. The Poles, suspecting that they are being led on a false trail, question Susanin closely. At dawn, knowing that by now the Tsar will be safe, Susanin confesses his deception. The Poles fall upon Susanin and kill him, but not before he has seen the first rays of sun and knows that he has succeeded. Sobinin and his friends arrive and attack the Poles.

Aria ‘You will come, my dawn?’ (A Life for the Tsar, Act IV)

Susanin’s recitative and aria is one of the most intense dramatic opera episodes. The image of Susanin as a patriot and hero is depicted in this aria. The aria begins with a full emotion melodious recitative They sense the truth! (Tchujut pravdu!).

Aria ‘They sense the truth!’ (A Life for the Tsar, Act IV)

Red square in Moscow. Stage design for the opera A Life for the Tsar by M. Glinka, 1939.

Epilogue. Red square in Moscow

A rejoicing crowd is awaiting the arrival of the Tsar. An exultant crowd acclaims the new Tsar, while Antonida, Sobinin and Vanya lament the death of Susanin passionately. Soldiers tell them that the Tsar will not forget their father’s sacrifice. Bells ring out as the Tsar approaches. All sing the hymn Glory to thee our Russian Caesar (Slavsya, slavsya, nash russkiy Tsar).

Glory to thee our Russian Caesar (A Life for the Tsar, Epilogue)

RUSLAN AND LYUDMILA

After the immensely successful premiere of A Life for the Tsar in 1836, Mikhail Glinka began almost immediately on his next opera Ruslan and Lyudmila, based on the mock-epic poem by Alexander Pushkin. The idea was suggested to Glinka by the playwright and theatrical official Alexander Shakhovskoy. Glinka hoped to work with Pushkin in person, but the great poet lost his life in a duel. The issue was the alleged infidelity of Pushkin’s wife, Natalya Goncharova, a famous beauty who had many admirers, including the Tsar himself.

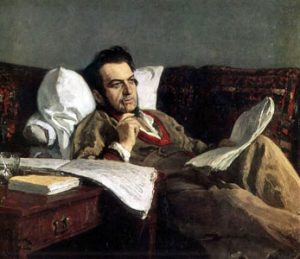

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka during the composition of the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila, 1887. Artist: Ilya Repin

Pushkin’s story stirred Glinka’s musical imagination. Glinka began to compose his opera before a libretto had been written. The verses of the libretto were written by Valerian Shirkov (with minor contributions by Nikolay Markevich, Nestor Kukolnik, Mikhail Gedeonov and the composer). It took Glinka six years to write Ruslan and Lyudmila. Glinka was forced to make frequent interruptions in his work. From 1837 to 1839 he served as director of the Imperial Chapel, a responsibility that was not to his liking. Another obstacle was his marital crisis. Glinka’s personal life during the opera’s creation was pretty miserable, owing to the infidelities of his wife; they separated at the end of 1839.

By the beginning of 1842 the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila was complete. When the opera finally had its public premiere on November 27, 1842 [November 9, New Style] at the Bolshoi Theatre in St. Petersburg, it was not well-received by the public and critics. Nicholas I (Russian Emperor in 1825–1855), left in an emphatic manner before the opera actually finished. The opera was declared a failure. The growing success of Italian opera in St. Petersburg gave this Russian-inspired work little chance. After 1848, Ruslan and Lyudmila wasn’t performed again during Glinka’s life.

Ruslan and Lyudmila was significantly more successful in its first season than many people realize. With the perspective offered by time, the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila is now generally acknowledged as a significantly superior work.

Synopsis

Act I The court of Svetozar, Prince of Kiev

He is holding a great feast to honor the marriage of his beautiful daughter Lyudmila and the brave knight Ruslan. The guests at the banquet include two of Ruslan’s rivals, Ratmir and Farlaf, who would like to see themselves as Lyudmila’s husbands. The Bayan (a bard) sings a prophetic song of the forthcoming trials for Ruslan and Lyudmila, though he predicts the victory of true love. All sing the praises of the bridal pair and toast Svetozar.

Ruslan and Lyudmila. Postcard, 1966.

Then Bayan sings another song (‘There is a desert land’ Yest’ pustynnyy kray) about a young singer whose lot it is to sing the fame of Ruslan and Lyudmila (Glinka intended this song as a memorial to Pushkin). Lyudmila bids farewell to her parent’s home (Cavatina, ‘I'm sad, dear father!’ Grustno mne, roditel’ dorogoy!), and consoles her unsuccessful suitors Ratmir and Farlaf. Svetozar blesses Ruslan and Lyudmila. The chorus sings the wedding song. Suddenly, darkness descends and Lyudmila vanishes. Svetozar promises his daughter’s hand and half his kingdom to any man who can rescue and bring her back. Ruslan, Ratmir and Farlaf rush off to find abducted maiden. The search begins.

Act II

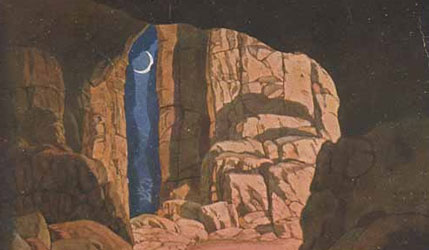

Finn’s cave. Stage design for the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila by M. Glinka, 1900. Artist: Ivan Bilibin

Scene 1. Finn’s cave in the mountains

A benevolent sorcerer Finn greets Ruslan and reveals that Lyudmila’s abductor is the nasty old sorcerer Chernomor and advises him to beware the evil sorceress Naina. Finn recounts the story of his own unhappy courtship of Naina, and reveals that she is very wicked. He indicates to Ruslan that good fortune lies to the north. Encouraged by the sorcerer’s words, Ruslan continues his journey.

Scene 2. A desert place

Farlaf meets the sorceress Naina, she promises to help him find Lyudmila and defeat Ruslan. Naina sends him home and asks to do nothing; she will take care of everything. Farlaf rejoices (Rondo, ‘My hour of triumph is near’ Blizok uzh chas torzhestva moyego).

Ruslan and the Head, 1879. Artist: Ivan Kramskoy

Scene 3. A deserted battlefield

The whole field is covered with fragments of weaponry: shields, swords, lances, helmets; and also human bones. Ruslan inquires: ‘O field, who has bestrewn thee with dead bones?’ (O pole, pole, kto tebya useyal mertvymi kostyami?). The empty dead field fills him with intimations of failure and mortality. As the fog dissipates, Ruslan sees before him the sleeping gigantic Head. It (represented by a unison male chorus) awakens. Ruslan confronts the Head, whose breath produces a tremendous wind, attempting to blow him down. Ruslan throws his lance into the Head, it yields up a magic sword. The Head launches into its narrative (‘We were two, my brother and I’ Nas bylo dvoye, brat moy i ya), from which Ruslan learns that the Head’s brother is Lyudmila’s abductor, evil sorcerer Chernomor whose strength lies in his enormously long beard and only with a magic sword, that Ruslan now holds, the dwarf Chernomor can be defeated.

Act III Naina’s enchanted castle

Naina’s castle. Stage design for the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila by M. Glinka, 1900. Artist: Ivan Bilibin

The evil sorceress decides to distract the knights who are looking for Lyudmila. There she intends to destroy them. Ratmir approaches the castle, the beautiful maidens sing a Persian song to enchant him (‘The dark of night settles over the plain’ Lozhit’sya v pole mrak nochnoy). Naina and the maidens disappear. Gorislava, one of Ratmir’s former lovers who is full of woe because he has deserted her, enters and bewail her fate (Cavatina, ‘O splendid star of love’ Lyubvi roskoshnaya zvezda), then she leaves. Ratmir enters, he is exhausted from his long journey (Aria, ‘Sultry heat has supplanted shade of night’ I zhar, i znoy smenila nochi ten’). The dancing of Naina’s slave girls hypnotizes him into forgetting his quest. Ruslan arrives, and at once falls in love with Gorislava, he too forgets Lyudmila. Finn appears and the two knights are saved, he breaks the spell of the enchanted castle. All maidens disappear, Naina’s castle turns into a forest. Ruslan moves on, and Ratmir becomes reconciled with Gorislava.

Act IV Chernomor’s magic gardens

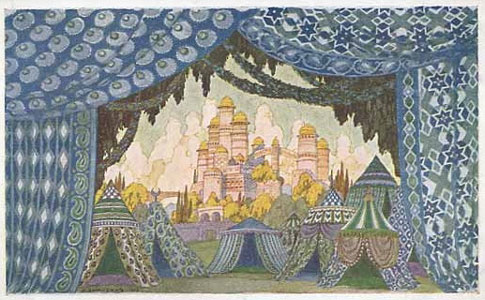

Chernomor’s palace. Stage design for the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila by M. Glinka, 1900. Artist: Ivan Bilibin

The evil sorcerer Chernomor puts Lyudmila in his beautiful palace with a great garden where she can walk anytime she wants and enjoy exotic flowers and fairy birds, but she is very unhappy in captivity, she misses her beloved Ruslan. Lyudmila bemoans her fate (Aria, ‘Far from my beloved and constrained’ Vdali ot milogo, v nevole). She tries to throw herself in the river, but the water maidens restrain her. Lyudmila rejects the advances of sorcerer. Chernomor’s March sounds, perhaps, it’s the most famous episode of the opera. Then come the Oriental dances, the first is Turkish; the second is an Arab dance, the most distinguished of three and the third the famous Caucasian Lezginka. Military signals announce the arrival of Ruslan. Chernomor casts a magical spell over Lyudmila and puts her into an enchanted sleep before going off to do battle with Ruslan. The knight defeats Chernomor by cutting off his enormous beard – the source of all his power – with the magic sword. Ruslan finds his beloved who is still unconscious, he is unable to awaken her. Ruslan decides to take her back to Kiev.

Chernomor’s gardens. Stage design for the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila by M. Glinka, 1913. Artist: Ivan Bilibin

Act V

Scene 1. Moonlit steppe

On the way to Kiev, Ruslan with enchanted Lyudmila, Ratmir and Gorislava, and former Chernomor’s slaves decide to take rest. Ratmir is standing watch over the caravan by night, former Chernomor’s slaves rush in with terrible news: Farlaf has abducted unconscious Lyudmila and is carrying her back to Kiev, Ruslan has gone in pursuit. Finn appears and hands Ratmir a magic ring that can awaken Lyudmila. Ratmir promises give the ring to Ruslan.

Scene 2. The court of Svetozar in Kiev (the same as in the first act)

Lyudmila is lying on a bridal bed surrounded by Svetozar, Farlaf, courtiers, slave girls, nannies, mothers, children, bodyguards, troops and people. There is a chorus of lamentation (‘Lovely Lyudmila, come to, awaken! ’Akh ty, svet Lyudmila, probudisya!). Farlaf fails to awaken Lyudmila despite Naina’s help, he flees when the hoof-beats are heard from the distance. Ruslan, Ratmir and Gorislava rush in. Ruslan puts a magic ring on her finger and Lyudmila opens her eyes. The chorus praises the gods, the homeland, Ruslan and Lyudmila. All rejoice. The wedding feast is resumed.

SHEET MUSIC:

You can find and download free scores of the composer:

Romances and Songs

-

- DANCE (WALTZ), Act II of the opera IVAN SUSANIN

- TARANTELLA

- CHILDREN’S POLKA (DETSKAYA POL’KA)

- RAZLUKA (SEPARATION), Nocturne

- WALTZ in E-flat major

- VARIATIONS on a Russian Theme

- VARIATIONS on Alyabyev’s Song “THE NIGHTINGALE”

- VARIATIONS on a Scottish Theme

- REMINISCENCES OF A MAZURKA

- MY HARP (MOYA ARFA)

- DO NOT TEMPT ME NEEDLESSLY (NE ISKUSHAY MENYA BEZ NUZHDY)

- THE POOR SINGER (BEDNYI PEVETS)

- CONSOLATION (UTESHENIYE)

- AH MY DEAR FAIR MAIDEN (AKH, TY, DUSHECHKA, KRASNA DEVITSA)

- HEART’S MEMORY (PAMYAT’ SERDTSA)

- LE BAISER (YA LYUBLYU, TI MNE TVERDILA)

- BITTER IT IS FOR ME (GOR’KO, GOR’KO MNE, KRASNOY DEVITSE)

- TELL ME WHY (SKAZHI, ZACHEM)

- POUR UN MOMENT (ODIN LISH’ MIG)

- WHY DO YOU CRY, YOUNG BEAUTY? (CHTO, KRASOTKA MOLODAYA)

- MI SENTO IL COR TRAFIGGERE (TOSKA MNE BOL’NO SERDTSE ZHMET)

- HO PERDUTO IL MIO TESORO (SMERTNYY CHAS NASTAL NEZHDANNYY)

- TU SEI FIGLA (SKORO UZY GIMENEYA)

- PUR NEL SONNO (YA V VOLSHEBNOM SNOVIDEN’YE)

- PENSA CHE QUESTO ISTANTE (VOLEY BOGOV YA ZNAYU)

- DOUVUNQUE IL GUARDO GIRO (KUDA NI VZGLYANU)

- PIANGENDO ANCORA RINASCER SUOLE (KAK V VOL’NYKH PROSTORAKH)

- MIO BEN RICORDATI (YESLI VDRUG SRED’ RADOSTEY)

- O DAFNI CHE DI QUEST’ANIMA AMABILE DILLETTO (O DAFNA MOYA PREKRASNAYA)

- AH, RAMMENTA, O BELLA IRENE (VSPOMNI, O IRENA)

- ALLA CETRA (K TSITRE)

- DISENCHANTMENT (RAZOCHAROVANIYE)

- DEDUSHKA! – DEVITSY RAZ MNE GOVORILI

- SING NOT, BEAUTY, IN MY PRESENCE (NE POY, KRASAVITSA, PRI MNE)

- SHALL I FORGET (ZABUDU L’ YA)

- VOICE FROM ANOTHER WORLD (GOLOS S TOGO SVETA)

- IL DESIDERIO (ZHELANIYE)

- THE WINNER (POBEDITEL’)

- VENETIAN NIGHT (VENETSIANSKAYA NOCH’)

- L’INIQUO VOTO (V SUDE NEPRAVOM), Aria

- DO NOT SAY LOVE WILL PASS (NE GOVORI LYUBOV’ PROYDET)

- SOUNDS OF THE GROVE (DUBRAVA SHUMIT)

- CALL HER NOT HEAVENLY (NE NAZYVAY YEYE NEBESNOY)

- I HAD BUT RECOGNIZED (TOL’KO UZNAL YA TEBYA)

- I AM HERE, INEZILLA (YA ZDES’, INEZIL’YA)

- THE NIGHT REVIEW (NOCHNOY SMOTR)

- I RECALL A WONDERFUL MOMENT (YA POMNYU CHUDNOYE MGNOYEN’YE)

- OH, IF I HAD KNOWN… (AKH, KOGDA B YA PREZHDE ZNALA…)

- VIRTUS ANTIQUA (RYTSARSKIY ROMANS)

- THE FIRE OF LONGING BURNS IN MY HEART (V KROVI GORIT OGON’ ZHELAN’YA)

- DOUBT (SOMNENIYE)

- THE LARK (ZHAVORONOK)

- STRONG WIND BLOWS ACROSS THE FIELD (HUDE VITER VELʹMY V POLI)

- THE NORTH STAR (SEVERNAYA ZVEZDA)

- OH, MY WONDERFUL MAID (O, DEVA CHUDNAYA MOYA), Bolero

- DECLARATION (PRIZNANIE)

- TO HER (K NEY)

- THE NIGHT ZEPHIR (NOCHNOY ZEFIR)

Opera A LIFE FOR THE TSAR (Zhizn’ za tsarya; Ivan Susanin)

Opera in 4 Acts with a Prologue. Text by S. Gorodetsky. Vocal Score.

Russian and Polish choruses; peasants, gentry, soldiers, crowd.

Setting Russia and Poland, 1612-1613

ACT I

- №1. Introduction

- №2. Antonida’s Cavatina and Rondo

- №3. Scene and Chorus

- №4. Scene, Tercet and Chorus

ACT II

- №5. Polonaise

- №6. Krakowiak

- №7. Waltz

- №8. Mazurka and Finale

ACT III

- №9. Entr'acte

- №10. Vanya's Song

- №11. Scene and Vanya’s and Susanin’s Duet

- №12. Peasants’ Chorus

- №13. Quartet

- №14. Scene and Chorus

- №15. Wedding Chorus

- №16. Antonida’s Romance

- №17. Finale of the Third Act

ACT IV

- №18. Entr’acte

- №19. Chorus and Sobinin’s Aria

- №20. Vanya’s Recitative and Aria with Chorus

- №21. Scene and Chorus

- №22. Susanin’s Aria

- №23. Recitative and Finale

EPILOGUE

- №24. Entr’acte

- №25. Chorus, Scene and Trio

- №26. Finale

Opera RUSLAN AND LYUDMILA

Fairy opera in five Acts. Libretto by V. Shirkov and M. Glinka. After a poem by A. Pushkin. Vocal Score.

ACT I

- №1. Introduction

- №2. Lyudmila’s Cavatina

- №3. Finale

ACT II

- №4. Entr’acte

- №5. Finn’s Ballad

- №6. Duet of Finn and Ruslan

- №7. Scene and Farlaf's Rondo

- №8. Ruslan’s Aria

- №9. Scene with the Head

- №10. Finale. Tale of the Head

ACT III

- №11. Entr’acte

- №12. Persian Chorus

- №13. Scene and Gorislava’s Cavatina

- №14. Ratmir’s Aria

- №15. Dances

- №16. Finale

ACT IV

- №17. Entr’acte

- №18. Scene and Lyudmila’s Aria

- №19. Chernomor’s March

- №20. Oriental dances:

- Turkish

- Arabian

- Lezginka

- №21. Chorus

- №22. Finale

ACT V

- №23. Entr’acte

- №24. Ratmir’s Romance

- №25. Ratmir’s Recitative and Chorus

- №26. Duet of Finn and Ratmir

- №27. Finale

0 Comments